herzog's visions of vancouver

Visions of Vancouver

Over the decades, Fred Herzog's photos of the city have captured an evolving metropolis

The Vancouver Sun

Saturday, January 27, 2007

By John Mackie

FRED HERZOG: Vancouver Photographs Vancouver Art Gallery

Until May 13, 2007

It's hard to imagine anyone who loves Vancouver not loving Fred Herzog's photographs. For five decades, he has artfully documented the city, walking the streets with his camera to capture day-to-day life.

Herzog's vision was to see art in almost anything: a family sitting outside on a summer's day, a Volkswagen Beetle turning the corner in the rain, a wall of photos of men's hairstyles in a Main Street barber shop. He shot billboards, second-hand stores and store window displays, neon signs, the working waterfront and people.

His photos are so lifelike, so true to life, it's stunning. His goal was to capture real life, and he succeeded.

Herzog's 1958 photo of the hub-bub of street life on Hastings Street at Columbia is arguably the best photo ever taken showing the Hastings strip in its prime, before its long, slow decline into the epictentre of the troubled Downtown Eastside.

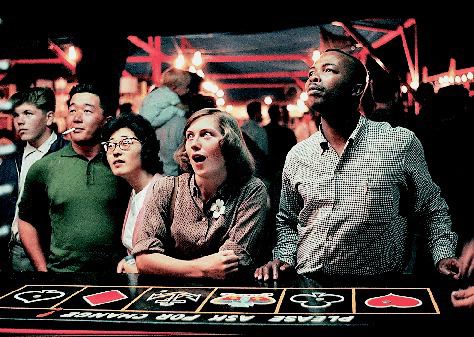

The 1958 nighttime shot of the neon jungle at Hastings and Columbia is the premier illustration of the days when Vancouver was a neon mecca. His 1961 photo of gamblers playing the Crown and Anchor game at the Pacific National Exhibition is simply the best PNE photo, ever: the expectant look on a woman's face as the gambling wheel comes to a stop is just priceless.

Photos like this have made the 76-year-old Herzog something of a legend in Vancouver photography circles.

"In the history of art photography in Vancouver, the first major figure is John Vanderpant in the '20s and '30s," says internationally acclaimed photographic artist Roy Arden. "And then you have Fred in the '50s and '60s."

But precious few people have ever seen his photos. Though he's been photographing the city since 1953, Herzog has had only a handful of gallery exhibitions, and no major survey of his work since the 1960s.

This is about to change. On Thursday, the Vancouver Art Gallery unveiled Fred Herzog: Vancouver Photographs, a retrospective show featuring 140 photographs from the 1950s to today. The show was a hit before it even opened, drawing a torrent of local press coverage.

Vancouver Art Gallery curator Grant Arnold understands the appeal.

"His subject matter cuts across a whole range of interests in terms of depicting the city," says Arnold, who put together the show with Herzog.

"It's kind of amazing at the different levels people relate to his images on."

People who lived through the era he photographed have a strong emotional reaction to his photos. Those who didn't will be amazed at the bustling, chaotic port city that was once Vancouver.

Part of the reason his photos are so startling is that they are in colour. When Herzog started shooting in the 1950s, all serious art photography was done in black and white. But Herzog opted to shoot colour slides in Kodachrome, which gave rich, lifelike colours.

"To do colour photographs in the 1950s in the art world was unthinkable," says Andy Sylvester of the Equinox Gallery, who will be mounting a show of Herzog's photos from the '50s and '60s on February 8th.

"The precedent in that kind of work would be Walker Evans and Robert Frank, and those people were dealing exclusively in black and white. That was the esthetic choice of the serious art world in the 1950s, with respect to photography. He ignored that, to his credit. Which I'm sure took great courage.

"And when you look at his proof prints, he worked all the time. He photographed as much as he could. That's usually the secret of important photographers, when you look at their body of work, you say they worked all the time. Someone like Lee Friedlander doesn't stop. The same with Fred. He persevered, period, whether he was getting praise or no praise."

"He developed his own realism, his own style, and that's not an easy thing to do," Arden says.

"It looks easy -- when it's good, it looks easy. But it's not easy, it's very very hard. People always talk about [his photos] as if it was just some transparent document of a subject, [but] he should be given some credit for the art of his photographs."

There was another reason Herzog chose to make Kodachrome slides: They were cheaper, because you could send them to a Kodak lab rather than having your own darkroom. Cost was important because Herzog's city photographs were done in his spare time, and paid for out of his own pocket. Herzog was never a full-time artist: he made his living as a medical photographer.

Herzog was born in Stuttgart, Germany on Sept. 21, 1930, and lost both his parents when he was young (his mother died of typhoid in 1941, while his father survived the Second World War only to die of cancer just after it ended). Money was tight in post-war Germany, and he dropped out of high school to go to work. In 1952, he emigrated to Canada, living in Toronto for a year before settling in Vancouver.

He worked as a seaman for Union Steamships when he first arrived in Vancouver, and credits the long voyages to Alaska with completing his education (he would read books to while away the hours). He had first picked up a camera in 1950, and in Canada was encouraged by his friend Ferro Marincowitz to take up medical photography. He volunteered at hospitals, living off his savings from the ships, but eventually landed a job at St. Paul's Hospital and then UBC, where he worked from 1961 to 1990.

One of of Herzog's earliest champions was the legendary conceptual artist and photographer Iain Baxter&, of N.E. Thing Company fame. He thinks Herzog's day job had an impact on the way he shot Vancouver.

"Fred has an amazing way of looking at a city, because he was a medical photographer," says Baxter&, who hired Herzog to teach photography at Simon Fraser University in the late 1960s.

"I think in a way that's how he really analyses a city. He has a very interesting clinical way that he can go into a city, but it's imbued with humanity as well. He [has] an unusual way of looking at a city as an organism, as a living body almost."

You can see this in Herzog's shot of a jumble of street signs, business signs and signs painted on the sides of buildings at Carrall and Hastings in 1968. Or in his photo of the Hastings neon jungle a decade earlier, where you can almost smell the aroma from the White Lunch's bright orange neon coffee cup, a blue twirl of steam rising into the night.

"Signs expressed the vitality of a city," Herzog says.

"You notice that now the city has no signs, the vitality is no longer visible. It may be in the dining room or the kitchen or the bedroom, but not in the city."

Hastings and Carrall was the site of another great shot showing the vitality of the city, two friends sharing a laugh on the street.

"It's called The Joke, and it isn't [technically] sharp," Herzog says.

"But look at the fun these guys are having. He's patting [the other guy] on the belly, saying, 'What about that now, guy?' And he breaks up laughing. Isn't that wonderful? That shows a warmth, the way people used to be out in the city. It said 'This is our city,' where we could be ourselves and have enjoyment and meet friends.

"It's not like that now. There's an atmosphere of fear here, of dereliction, of drugs. It's just awful. And we've made it that way, nobody can say that just happened. We made it that."

Herzog is very proud of photographs like this. Because of the limitations of colour film at the time, it was technically daunting to take on-the-fly street photos.

"I'm still amazed at how Fred was able to get anything, given the materials he used," says the VAG's Arnold. "Because he used a very slow film, [and] very very slow shutter speeds."

Herzog is amazed at some of the shots he got himself, such as a photo of two kids joyously fighting over a piece of bubblegum.

"I have two pictures of that," he says.

"This one, I took it at full aperture, on ISO 10 film. Do you know what that means? Films now have ISO 800 or even more, 1600. This was so slow, I had to shoot the picture at full aperture, F2, and a tenth of a second. And that's how it turns out, and it's good.

"[But] I said to them, 'I'm not sure if I got this picture of you guys, could you do it for me again?' And of course, it's so stiff and acted, it has no value at all. You couldn't even show it to your own mother. That [first] picture has the authenticity of observed life. To me that is the key to success in photography."

Technical know-how is one thing, but Herzog also had a great eye.

"Fred has a really kind of uncanny ability to render bodily gesture," says Arnold.

"He has a real amazing sensibility for that. So much of the meaning of his photographs is conveyed through bodily gesture and the positioning of the body."

This can be very subtle, such as Herzog's photo of a young woman out on the town at the PNE in 1960. The look in her eyes, the spot of lipstick on the cigarette she holds in her hand, even the slightly blurred image truly capture the moment in time.

"I even like her," says Herzog.

"If she had lived across the hall, something would have happened. There is an archetypal North American personality here which grips me. I have such love and sympathy for her, because she went out at night. Look how she's prettied up. She came here and said 'I'm going to hit the town, in my own modest way.' She has both a presence and a slight sense of abandonment. The way she has her cigarette, she's got style. She is not one of the types you would say is a film star, but I'd like to use her in a movie."

The image of the young woman at the PNE is among 80,000 slides and 28,000 black and white negatives Herzog has been going through for the show.

"I have not had a holiday in the last four years, because I have worked 10 hours a day on this show," he says.

"It's a lot of work, an unbelievable amount of work to make [digital] scans, to approve the proofs, to print them, to reprint them if they're not right. And to learn how to do it.

"All that has taken four years of my old life. But it has also in a way revived me. You could die of boredom, let's face it. And this prevented that outright."

Herzog is also relieved that people finally seem to have caught on to what he was doing.

"These [photos] would have disappeared if we had not done this [VAG] show," he says.

"I've even said to my wife, 'If you have to dump those, don't dump them all on the same day.' Nobody wanted them. It's colour. I offered them to the National Gallery [in the early '80s], and they said 'Sorry, we only do black and white.'"

There are also some advantages to being finally discovered by the masses at this time. Technology has advanced to the point where the perfectionist Herzog could finally get the type of colour prints he wanted, at a reasonable price.

"That's from the '60s," he says, pointing to a picture.

"Look at how that can be resurrected through the digital method. If I had had to do a show then, I simply could not have afforded it, it would have cost 10 times as much and it wouldn't have been as good. All the factors that lead to a good show have come together now.

"At my age, 76, perhaps it would have been nice to have that at age 60 or so. But I'm glad, I'm happy, I'm proud. I think actually it's better it's now, because I think it would have changed my life [to have success earlier]. Instead of taking pictures I would have sat around at parties."

--

John Mackie will team up with heritage expert Norman Young to lead a tour of photographs by Fred Herzog (pictured below) at the Vancouver Art Gallery on February 25 at 2 pm.